Composition with Twelve Tones:

Chapter 11

Obviously, the requirement to use all the tones of the set is fulfilled whether they appear in the accompaniment or the melody. My first larger work in this style, the Piano Suite, op. 25, already takes advantage of this possibility, as will be shown in some of the following examples. But the apprehension about the doubling of octaves caused me to take a special precaution.

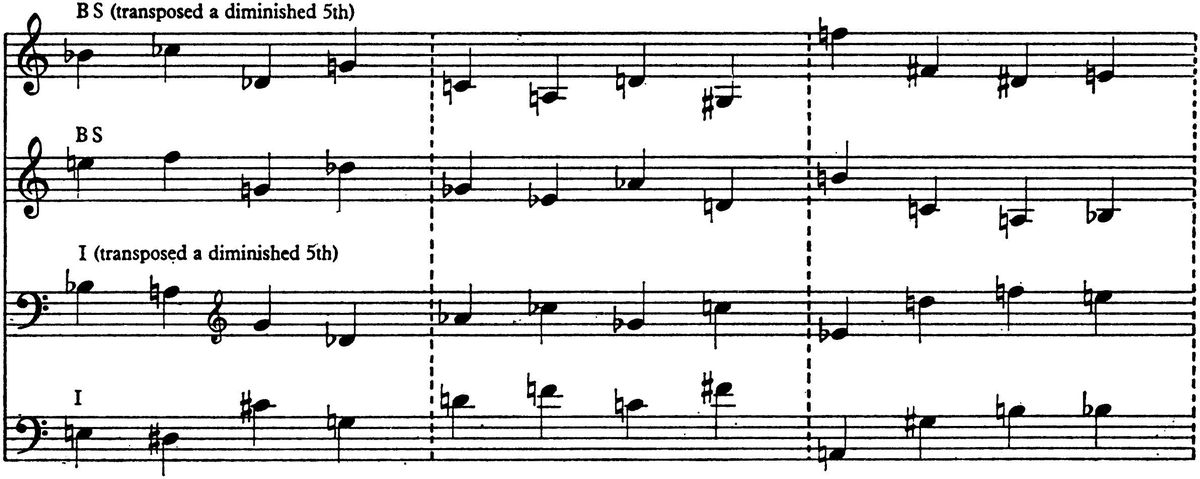

Example 13:

Example 13a:

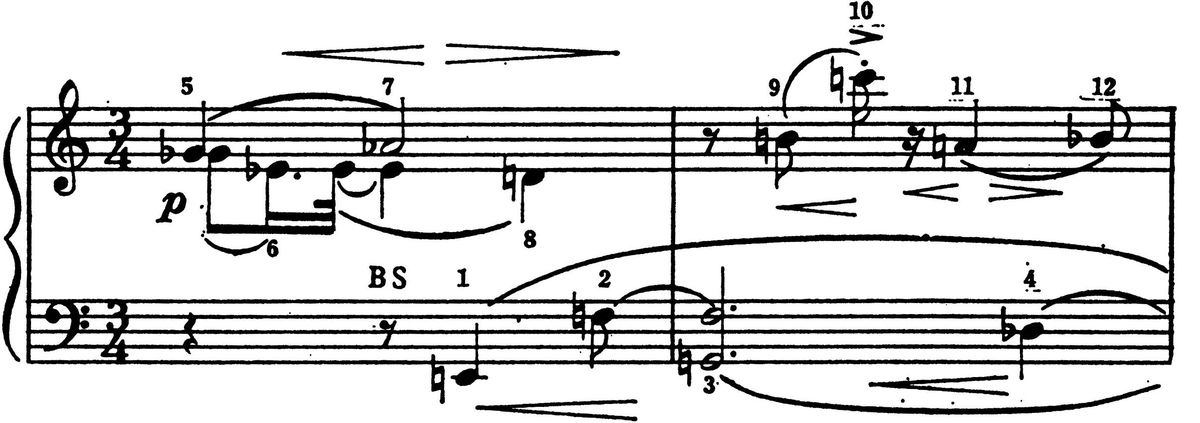

The BS as well as the inversion is transposed at the interval of a diminished fifth. This simple provision made it possible to use, in the Praeludium of this Suite, BS for the theme and the transposition for the accompaniment, without octave doubling.

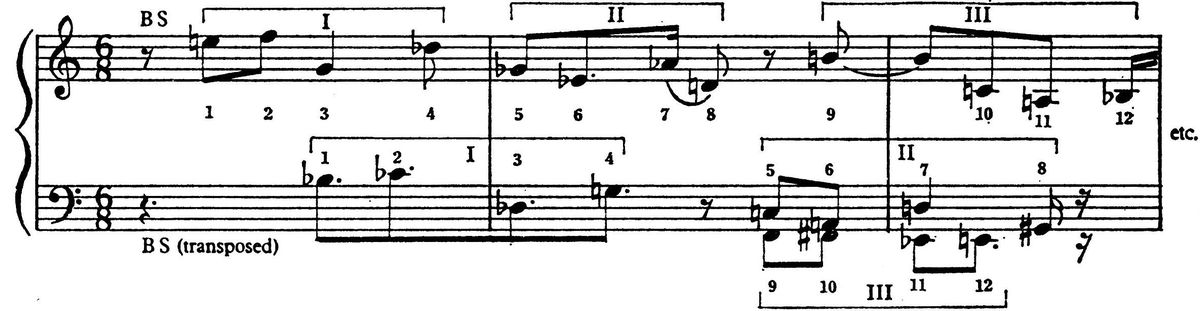

Example 14:

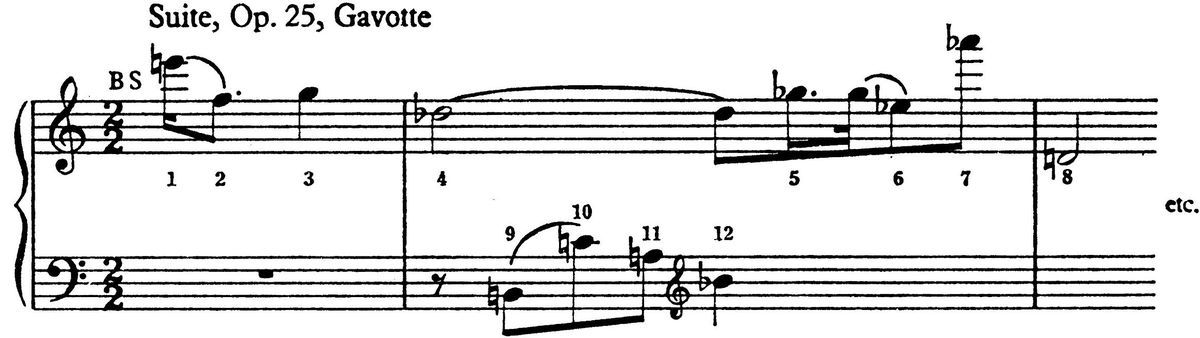

Example 14a:

But in the Gavotte (Example 14) and the Intermezzo (Example 14a) this problem is solved by the first procedure mentioned above: the separate selection of the tones for their respective formal function, melody or accompaniment. In both cases a group of the tones appears too soon – 9-12 in the left hand comes before 5-8. This deviation from the order is an irregularity which can be justified in two ways. The first of these has been mentioned previously: as the Gavotte is the second movement, the set has already become familiar. The second justification is provided by the subdivision of the BS into three groups of four tones. No change occurs within any one of these groups; otherwise, they are treated like independent small sets. This treatment is supported by the presence of a diminished fifth, Db – g, or g –Db, as third and fourth tones in all forms of the set, and of another diminished fifty as seventh and eighth tones. This similarity, functioning as a relationship, makes the groups interchangeable.

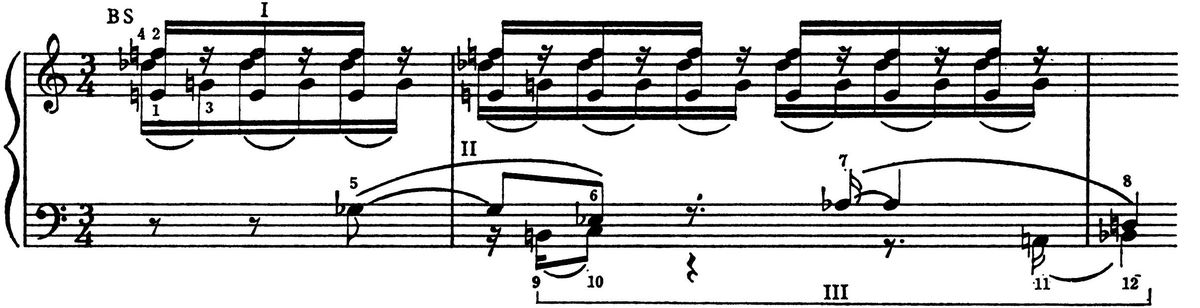

Example 15:

Example 15a:

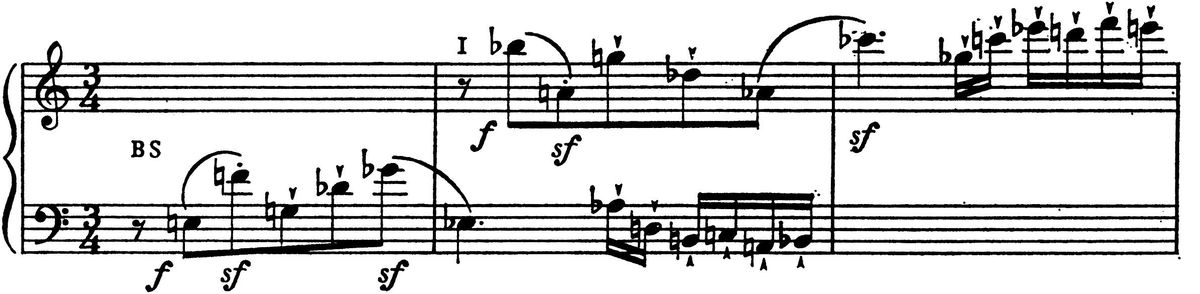

In the Menuet of the Piano Suite (Example 15) the melody begins with the fifth tone, while the accompaniment, much later, begins with the first tone.

The Trio of this Menuet (Example 15a) is a canon in which the difference between the long and short notes helps to avoid octaves.

The possibility of such canons and imitations, and even fugues and fugatos, has been overestimated by analysts of this style. Of course, for a beginner it might be as difficult to avoid octave doubling here as it is difficult for poor composers to avoid parallel octaves in the "tonal" style. But while a "tonal" composer still has to lead his parts into consonances or catalogued dissonances, a composer with twelve independent tones apparently possesses the kind of freedom which many would characterize by saying: "everything is allowed." "Everything" has always been allowed to two kinds of artists: to masters on the one hand, and to ignoramuses on the other. However, the meaning of composing in imitative style here is not the same as it is in counterpoint. It is only one of the ways of adding a coherent accompaniment, or subordinate voices, to the main theme, whose character it thus helps to express more intensively.